Judy Ledgerwood

1301 PE

Closed April 20, 2010

There is a passage in my favorite art biography, Seeing is Forgetting The Name of the Thing on Sees, where Robert Irwin comes up against the mysterious world of what he calls “power” in painting. He experiences an odd moment of comparison, specifically a large James Brooks with “five major shapes in it” in contrast to a “funny little Guston kind of scrumbly painting.” Irwin was intimidated, infuriated, and humbled by that “goddamn Guston” – the Guston outwrestled and “just took over.” “The Brooks fell into the background,” Irwin said, “And I learned something about . . . some people call it ‘the inner life of the painting,’ all that romantic stuff, and I guess a way of talking about it. But shapes on a painting are just shapes on a canvas unless they start acting on each other and really, in a sense, multiplying. A good painting has a gathering, interactive build-up to it.”

I recently had a similar experience myself and it is bothering me. The story is basically this -- I’ve seen dozens of Judy Ledgerwood paintings in my life, mostly in

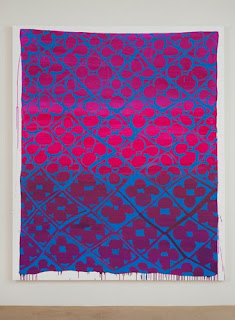

If I would add up my own list of bullet points, I would say a Ledgerwood is an interesting blend of optics (how your visual hardware works on a scientific level), the tension between decoration and abstraction (a jargony trap which I’ll discuss in a minute), and handmade joy. They are bright patterns, undulating like vertical waves at times, folding in on themselves at others, wrapping, and sometimes suspending their movements like fabric swinging from a laundry line. The smallest ones, my favorite being Tangarine sun and summer sea, 2010 (seen above) invite the eye almost like a pulsing button, growing bright then dark, waiting to be pushed, needing to be pushed, though the reason is unclear.

People rarely speak of power in painting anymore. Actually, they speak this way quite a lot, just not on paper and definitely not in any major art magazine. Admittedly, these moments of surprise and power when it comes to painting are hard to articulate and most of the terms that were coined to speak of it have now been discounted or at least are out of fashion. A modernist of the Michael Fried variety, for instance, would have described this power as “presence,” and will use phenomenology (sometimes Merleau-Ponty, sometimes Heidegger) to describe the moment -- how it aligns you to yourself (if this is possible), how you can be “in the painting,” suspended in and immersed in looking. This unifies the physical with the mystery and result is an extraordinary thing – a painting that justifies itself through explicating, enacting, and centering physical reality.

Other commentators, like Kurt Varnedoe, former MoMA curator of painting and sculpture, would maybe talk about the moment historically, that the power is a confluence of a particular program and history of painting that comes together into a new and fascinating area of connections. The parsing and categorizing brain, caught up in new networks of meanings, will feel overwhelmed.

The majority of official writers in the arts, however, make a living by beating a confession out of this moment without actually talking about it directly. “Presence” has been replaced by circumstantial and situated meaning. For instance, when Fried thinks that he is feeling something, a critical person would then say that the feeling is an illusion produced by a web of situations that put him in that particular place and there is no way to verify or guarantee that the feeling will ever happen again – there is no criteria for determining when this feeling should happen. A Jackson Pollock might as well be a pan of scrambled eggs, to use Rosalind Krauss’ informe track.

I suspect, and have been suspecting for sometime, that this way of thinking leads to another phenomenon, a way of talking around such moments that is endemic to much contemporary criticism. In order to explain away power, they arrange the painting in the middle of a variety of categories – between representation and abstraction, between design and formlessness (I did this earlier), between order and chaos, somewhere in the space between Pollock and tablecloths, between authenticity and simulation, between reality and illusion. The habit then is to show how the artist (insert name here) dodges these categories and presents something else, a viable hinterland in which you are not really standing but evaporating and being remade at each moment. Writers that take this track not only greatly exaggerate – for instance, does a Dash Snow collage of Saddam Hussein’s testicles really dodge categories and show us the contingencies of the visual experience, or is it just the secretions of an overgrown idiot? In other words, we explain away actual experience in favor of rhetoric that fits.

Now the belief is, I think, that having something fall in-between categories of assessment animates the art and gives it life, gives you a new space to think about that is not straightforward but instead a complicated thing. This is absolutely true. However, to truly exist in that space is a difficult thing. To be honest, when I view a Ledgerwood, I don’t feel in-between anything. The paintings simply are, and to move from that experience into rhetoric hurts both you and the painting in a way. I admit I am sympathetic to Fried’s reading of presence, and I am also partial to the way Bob Irwin looked at Guston. It seems we must talk about the fact that the image is acting on us in a physical manner and that the reality of that encounter is not merely a matter of tricks or illusions, nor is it a simple assertion of our optical hardware. What did Irwin mean when he spoke about shapes and colors acting on each other, why does the Ledgerwood button pulse for me? If it were simply a matter of optics and a scientific matter, then what rises up in me to resist this reading? Why do I then feel downright humbled by the fact that the images achieve this optical effect by gestures of the brush, casual patterns of the craftsman and not the machine?